Story by Rohit Brijnath/YOG News Room

Friday, August 20, 2010 — Coaches may not find time to read novelist Vladimir Nabokov, but his urging to writers to “caress the detail, the divine detail” is a philosophy they embrace in their own way. Every minor component matters when scripting sporting success.

An Olympic champion I know arrived at his first Games 10 days early. By competition time, he felt jaded. He learnt. At his second Games, he landed at midnight and got exhausted processing his accreditation. He learnt. Third Games, he won.

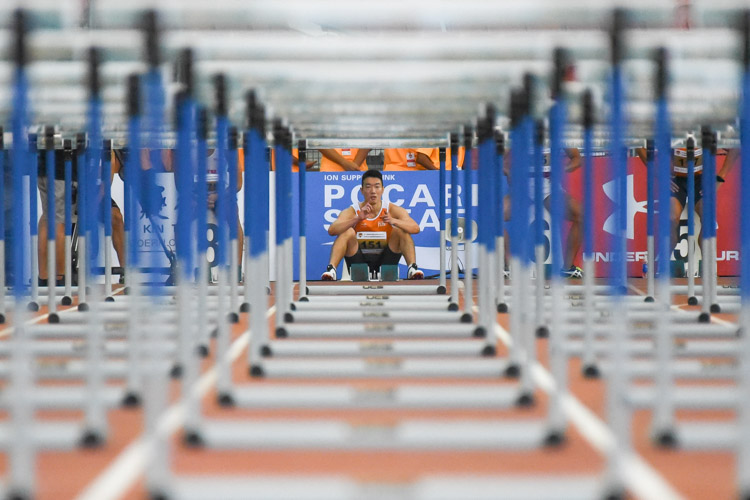

Had he experienced this young Games, it’s possible he may have won earlier. Because this is both Competitive Olympics – just watch the raw desire of the athletes – yet also Learning Olympics, one vast study group cramming for a future exam.

As Craig Redman, Australia’s national talent development manager in triathlon, puts it: “There is no such thing as an elite junior athlete. They are all developing elite athletes.”

These Games are a tutorial in detail, which helps teams, says Redman, so “that when they get to a real Olympics they are not blown away”.

Most athletes have never lived in a village. Dealt with security. Faced media. Undergone drug tests. Worn a national uniform. Or seen such a collection of draped flags outside windows that signify a world of talent is here.

It tests the focus, invades the mind, takes time, warrants patience. Nothing is irrelevant. In Atlanta 1996, the defending judo heavyweight champion David Khakhaleishvili was disqualified for missing his weigh-in because he got there late.

Redman, a triathlete professor of sorts, arrives from a nation that has a Phd in the triathlon.

Australia has produced the last three Ironman world champions. It has a tough national junior series. It owns a grassroots programme, sweetly dubbed TRYathlon, which starts with seven-year-olds whose event comprises a gentle 50m swim, 4km bike ride, 1.5km run. It is the beginning of a long and lively learning curve that continues in Singapore.

Redman advocates patience with his young Olympians, citing the old rule of 10 years or 10,000 hours of practice before expertise arrives. Of course medals matter, but for him if coaches make medals the sole priority they have failed.

His team may have won two silvers, but his focus is on teaching, on ensuring they graduate with a three-part degree.

First: “Learning to train.” Get the nutrition right, the psychology, the warm-up. Be ready.

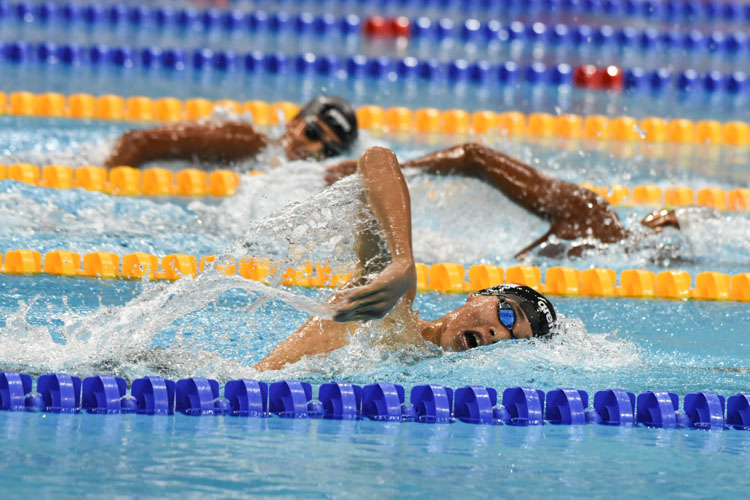

Second: “Learning to race.” An athlete delays a warm-up and must rush to his event and thus lacks adequate calm. Another loses his goggles early in the swim and faces irritation. Every minor error is costly.

Learning, says Redman, is also giving athletes “a few keys to think of” during races, mastering small arts, one at a time. “Focus on the first 200m of a swim to get good positioning.” Or “practise attacking on a bike, take a chance”.

The athlete’s brain is a computer, accumulating data. When it’s programmed, in two-three-four years’ time, the final part comes: “Learning to win.”

It is a sound theory. Which makes you wonder: Along with those medals, maybe they should hand out diplomas.

All this good advice will fall to deaf ears in Singapore because the national sports association is not keen in sport development at all and has advocated coach monopoly for more than a decade by the same coach who has produced no results. Which brings the question, what governance is there on the sport and it’s development stakeholders?